This week, we come not only to bury the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, known as Prohibition, but also to praise the 21st, which put a stake through the 18th's nasty dark heart just 14 years after its passage in 1919. Prohibition was enforced by a singularly bad piece of legislation called the Volstead Act which, although vetoed by Woodrow Wilson, was nevertheless overridden by a Republican congress, and which thus put D.C. muscle behind the "Noble Experiment" (Herbert Hoover's words) in bossing the American people around for their own good.

The 18th was the third of the four so-called "Progressive Era" amendments, which began in 1913 with the 16th (income tax) amendment and continued down its gruesome anti-freedom path that same year with the 17th amendment. As is typical of a Leftist policy mandate, the amendments purported to solve a relatively minor problem by creating an ongoing and very destructive large one.

After all, the country had managed very well during the first century of its existence by limiting the reach of the federal government into the states' prerogatives and the citizens' lives by restricting its access to revenue to excise duties and tariffs; similarly there was no urgent need to tinker with the Founders' carefully wrought structure of the Senate by effectively nationalizing the upper chamber via popular election rather than appointment by the state legislatures. In a single year, the entire relationship of both the states and the citizenry vis-a-vis the federal government had changed utterly and irrevocably.

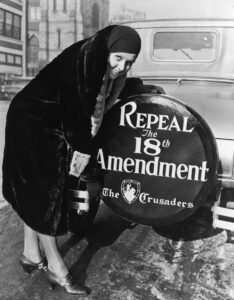

Down the drain it goes.

The 18th, and its homely sibling the 19th (also passed by Congress in 1919 and ratified by the states the following year) similarly dealt profound blows against the nation-as-founded. While it's true that the Founders had provided for altering the Constitution via the amendment process, they had not envisioned using that process as a battering ram against the very nature of the document itself.

The first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights, did not tamper with the main body of the 1789 Constitution; passed in 1791, it was more like a codicil of necessary afterthoughts and corrections (always in favor of personal liberty and less governmental power) after the principal job—creating a sturdy new nation out of whole cloth—had been accomplished. Other amendments, both before and since, were mostly concerned with various mundanities, such as the timing of federal elections and jurisdictional issues.

But just a century or so after the official founding of the Republic, busybodies from both parties decided the time had come for some "fundamental change." Led by three aggressive presidents—Teddy Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Wilson—Washington undertook an astonishing power grab—the legislative and political equivalent of the Supreme Court's self-serving Marbury v. Madison—whose deleterious effects still resonate today. The 18th reads:

Section 1

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.Section 2

The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The "appropriate legislation" was the Volstead Act, under the strictures of which, "no person shall on or after the date when the eighteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States goes into effect, manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, and all the provisions of this Act shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented."

Why is this wine different from all other wines?

The Volstead Act significantly added possession to its list of lifestyle crimes, which in the end was probably what ensured its demise. In New York, gangsters such as the British-born Irishman Owney Madden and Dutch Schultz (born Arthur Flegenheimer in the Bronx) made fortunes by assuming the risks of manufacture and sale of beer and profiting handsomely; Madden's brew, "Madden's No. 1" was the most popular brand of beer in New York City. They served their own booze in the nightclubs that sprang up to service thirsty customers; Madden himself owned the Cotton Club, where he employed Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Lena Horne; and the Stork Club, where he used Sherman Billingsley as the front man. Prohibition was not only a gift to gangland, but to American popular music as well.

Further, there were some legalized exceptions: kosher wine for Passover, for example, which led to such wonderfully ecumenical scenes as Irishmen lined up around the block in Manhattan to buy some kosher wine and thus help celebrate both Passover and St. Patrick's Day, two of the holiest days of the calendar on the Lower East Side.

The impulse behind Prohibition was of course the temperance movement and the Cleveland-based Women's Christian Temperance Union, a midwestern collective of hatchet-faced women agitating both against booze and in favor of women's suffrage. We think of Prohibition today as a quasi-moral crusade and ignore the suffrage part, but in the minds of the WCTU they were twinned.

In 1879, the formidable Frances Willard became president of the WCTU and turned to political organizing as well as moral persuasion to achieve total abstinence. Willard’s personal motto was “do everything.” The WCTU adopted this as a policy which came to mean that all reform was inter-connected and that social problems could not be separated. The use of alcohol and other drugs was a symptom of the larger problems in society. By 1894, under “home protection” the WCTU was endorsing women’s suffrage. By 1896, 25 of the 39 departments of the WCTU were dealing with non-temperance issues. However, temperance, especially in terms of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs, was the force that bound the WCTU’s social reforms together. To promote its causes, the WCTU was among the first organizations to keep a professional lobbyist in Washington, D. C.

And America heard the call.

A hidden element behind the passage of both the 18th and the 19th amendments was xenophobia. American had just experienced a huge wave of immigration from Europe, dirt-poor Irish, Italians, and Jews, which had followed an earlier movement of Rhineland Germans. Neither Catholics nor Jews were terribly popular among the WASP ascendency and the newcomers' fondness for the hop and the grape, combined with business acumen, was a selling-point behind Prohibition: a way to hurt the immigrants right in their own kitchens, parlors, bars, and social clubs. Because more immigrant voters eventually meant a loss of political power for the natives, something had to be done about it. (Sound familiar?)

Human nature being what it is, Prohibition soon turned out to be unenforceable. Places like New York City quickly gave up trying, and the police began acting as informants and enforcers for the gangsters, their clubs, and their breweries. Once, when the feds decided to raid Madden's brewery, the Phoenix Cereal Company on the 10th Avenue, in the heart of the Irish neighborhood of Hell's Kitchen, the cops tipped off Owney, who shut it down for evening, and ordered his men to park their cars up and down the avenue so that the feds would have to double-park in order to conduct their raid. While they were inside, the the NYPD ticketed and towed them.

Further, Americans were sickened by such outbursts of violence as the St. Valentine's Day Massacre in Chicago in 1929, a turf war between Al Capone's South Side Italians and Irish mobsters from Bugs Moran's gang on the other side of town. Seven people were machine-gunned to death. In New York Irish-born gunner Vincent's Coll's inadvertent murder of 5-year-old Michael Vengalli in heavily Italian East Harlem during a drive-by shooting on 107th Street in 1931 had the newspapers howling for Coll's head and giving him the monicker, Mad Dog Coll.

Things couldn't go on like this. Sentiment for Repeal burgeoned. As I have Owney Madden say in my American Book Award-winning novel (and his "autobiography"), And All the Saints:

By now, even the Feds had pretty much given up enforcing Prohibition, and Hoover trumped up a typical Goo-goo commission, this one named after some clown called Wickersham, to prove that what they thought had been such a swell notion just ten years earlier that they went and amended the Constitution was now a rotten idea and what they needed to do was, of course, amend the Constitution again. This, I thought, was the true genius of Goo-goos and reformers everywhere; that they never had to admit Reform was a mistake, and if it was, then all it took was more Reform to set it right.

Repeal had legs.

And so the 21st amendment was passed by popular acclaim in 1933, in the first year of the new Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration. It included this critical provision: "The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited." In other words, the regulation of alcoholic beverages was returned to the states, the same philosophy behind the recent Supreme Court Dobbs decision, which contrary to Democrat propaganda did not "outlaw" abortion, but simply returned the decision-making sovereignty back to the individual states. And that may be a clue as to how we might repeal many other amendments, laws, and court decisions: by returning to federalism.

In the meantime, America rejoiced: happy days were here again. And while the 18th had failed in its primary mission of reducing the political power of unfavored minorities (many of whom were immigrant men without wives), the Protestant establishment had already succeeded in passing what it thought was an even more powerful weapon to ensure its continued political dominance: the 19th amendment.

And here you thought that was about giving women the vote, but you never thought to ask why. We'll answer that question next week.

Article tags: 18th amendment, 19th amendment, 21st amendment, Dutch Schultz, FDR, Herbert Hoover, Owney Madden, Prohibition, Volstead Act, WCTU, Woodrow Wilson

Thus hooked, readly to be reeled in.

I have a few choice thoughts about #19, but will wait until I can savor yours next week.