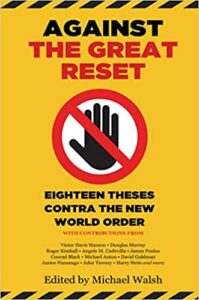

For the next two weeks, The Pipeline is presenting the remaining excerpts from each of the essays contained in Against the Great Reset: 18 Theses Contra the New World Order, which was published on October 18 by Bombardier Books and distributed by Simon and Schuster, and available now at the links.

Politics has always oscillated between Right and Left. After World War II, Western countries took many a step toward interventionism, regardless of warnings by a handful of intellectuals such as Friedrich Hayek and Michael Oakeshott. If the West went down the “road to serfdom,” that serfdom was bureaucratic, benevolent in its aims and generous with many. Yet in a few years, the consensus for growing interventionism was eroded, leading to the elections of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. In recent years, at least since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, politics have moved in the opposite direction, aiming to put an end to whatever “neoliberal policies” (as they came to be known in the public debate) a country ever pursued.

Yet with the Covid-19 pandemic, this process accelerated. Rahm Emanuel’s advice regarding the usefulness of a good crisis had a profound impact on the Western ruling classes: in the U.S. (where unprecedented and previously unimaginable levels of public spending have been reached), in the European Union (where the alleged need for stimulus policies allowed for the first-ever emission of common debt), in the Western hemisphere (where Covid-19 inspired unimaginable restrictions on the freedom of movement of the citizens). Hence, right from its beginning, the Covid-19 pandemic has been considered something more and different than simply a health crisis, however profound and indeed dramatic it’s been. In the pandemic, governments found (and, perhaps, searched for) an opportunity to address other problems. The pandemic was soon compared to a war and it was assumed that after it, like after war, we should “rebuild.” But “rebuild differently.”

How differently? Intellectuals and experts soon realized that it was their business to answer the question. Though the world in 2019 could hardly be seen as a laissez-faire paradise, a common cry has been a call for different institutions to plan, more solidly, from the top down. Technological transitions of the sort that are now typically advocated for (from the “green” economy to central bank digital currencies) indeed presuppose experts picking a technology. Yet the prevailing view seems not to be content with only industrial policies. The very nature of the economic system should change, moving from “shareholder” to “stakeholder” capitalism.

One element that differentiates this approach from previous waves of interventionism is that it goes hand in hand with a genuine revision of the political vocabulary. Think of the very locution “the Great Reset,” which acquired currency thanks to Professor Klaus Schwab, the influential founder and president of the WEF. The very use of those words implied (a) that the world needed a rebooting after the pandemic; (b) that such a rebooting could be done; and (c) that it could come about thanks to a specific set of policies. The discussion over these two terms includes a considerable toying with words.

Now on sale.

The Great Reset and the Stakeholder Model

Professor Klaus Schwab is a German-born economist that most people know as a highly successful entrepreneur: he is the founder and president of the WEF, a not-for-profit foundation headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. The WEF is most famous for its conferences, beginning with its annual Davos meeting, where business and political leaders reconvene to enjoy the company of some public intellectuals and ponder the world’s future. The WEF success put Davos on the map, and made the village—ten thousand in population, in the Swiss canton of Graubünden—a household name. In 2004, Samuel P. Huntington christened the participants “Davos men… a (then) new global elite… empowered by new notions of global connectedness.” They “have little need for national loyalty, view national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully are vanishing, and see national governments as residues from the past whose only useful function is to facilitate the elite’s global operations.”

In media accounts and in public perception, “Davos men” were at times seen as advocates of neo-liberalism, of globalization, of unfettered competition. This was a common misconception: equating the interest of companies and its moneyed classes with deregulation and competition, which most of the time, they dread. In one way, this was also quite naïve, even disingenuous: “crony capitalism,” meaning a system in which private companies and the government collude, is the greenhouse of the global elites. In fact, the spirit of the Davos meeting was always to bring all “stakeholders” around the table.

In Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and the Planet (written with Peter Vanham), Schwab, who coined the locution “the Great Reset,” suggested that we should “use the post-Covid-19 recovery to enact stakeholder capitalism at home, and a more sustainable goal economic system all around the world.” Why? And, in particular, why now? One would expect the aftermath of Covid-19 to see us all busy in getting back to what used to be “normalcy.” The time for reform should come later, not now.

Klaus Schwab: "you will own nothing and be happy."

The idea of “stakeholderism” isn’t new. Schwab himself has been advocating some version of it since the 1970s and is happy to provide an account of his own intellectual enterprise as a struggle against Milton Friedman. An important body of literature grew up around the theme, particularly in the field of business economics and corporate governance. Why should stakeholder capitalism be important in the wake of the pandemic? Why should we all go for it, particularly now? Why has the discussion about it moved out of the circles of experts, to include wider sections of society?

In part, these discussions were rejuvenated by the anniversary of an article published by Milton Friedman in the New York Times Magazine. Fifty years later, in the midst of a pandemic that saw an enormous growth of public spending, Friedman’s piece seemed the ideal starting point to launch a discussion regarding the future of business in the world’s economies. But this would have been a more academic, less heated discussion. Instead, important public figures like Schwab emerged to say that “free markets, trade, and competition create so much wealth that in theory they could make everyone better off… But this is not the reality we’re living in today.”

Schwab is a capable intellectual entrepreneur and a sharp mind. If he believes that “there are reasons to believe a more inclusive and virtuous economic system is possible—and it could be just around the corner,” this means that for him, the rethinking of the capitalist system is not necessarily more urgent because of the pandemic crisis, but such “reimagining” becomes easier, more within reach thanks to the growing role that governments have taken on during the lockdowns and other “emergency” measures. In other words, let’s not let a good crisis go to waste...

Next week: an excerpt from "History under the Great Reset," by Jeremy Black.

Article tags: Against the Great Reset, Alberto Mingardi, Covid-19, Davos, Klaus Schwab, The Great Reset, Wuhan virus

Why are Germans so evil?